About Project Tomato

About my game engine that has been under works for ~3 years.

For about 3 years, I have been working on a game engine under the name Project Tomato. The engine has undergone many backend changes, from basic OpenGL, to Vulkan, and finally, to bgfx.

Starting Out With raylib

While I have little to no screenshots of the engine at the start of development, I have some that show my growth throughout this development journey.

I started out working with raylib around then, which was a C library I had found out about from a PolyMars video, where he recreated the same game for 5 different consoles, translating his raylib code to work for said consoles.

Starting out with raylib back at the start of 2023 was crucial to my development journey, as it was easy to understand, which allowed me to focus more on learning the basics of C/C++ (since I was coming from Unity & C# )

My main issue with raylib was that it lacked crucial animation support for the project I had been working on. There were some projects that extended the abilities of raylib, but they were not maintained well, which eventually led to me moving away from using raylib for this project.

My experience with raylib was not bad, I just wanted more control over my rendering process, which led to me creating my own engine (even though raylib technically is not an engine, and I was still technically making my own engine on top of raylib anyway)

The First Iteration

Moving to OpenGL

My first attempts at creating a game engine were rough, as I wanted to do cross-platform development (mainly with homebrew for Nintendo Switch etc.)

Moving to Vulkan

While I used OpenGL, I wanted even more control over the rendering process, so I moved to Vulkan.

Vulkan was extremely difficult to grasp, as the code required to sufficiently use the library was extensive. The file I used for the rendering module ended up around 4000 lines by the end of my first iteration for this project, and most of it was written in about a weekend (which was filled with numerous errors and issues)

I also transitioned from using GLFW to using SDL for the window creation, input detection, etc.

The Real Work

The non graphical work on the engine really started to gain some traction in June-August 2023, where I was able to implement shadow rendering, PBR, and ray tracing (not RTX based, though)

Many issues I had regarded physics engines, as I switched between libraries often, starting out using ODE, then moving to Bullet for more maintained code, then moving to Jolt for GPU acceleration (which I never got to implementing), then eventually moving back to Bullet.

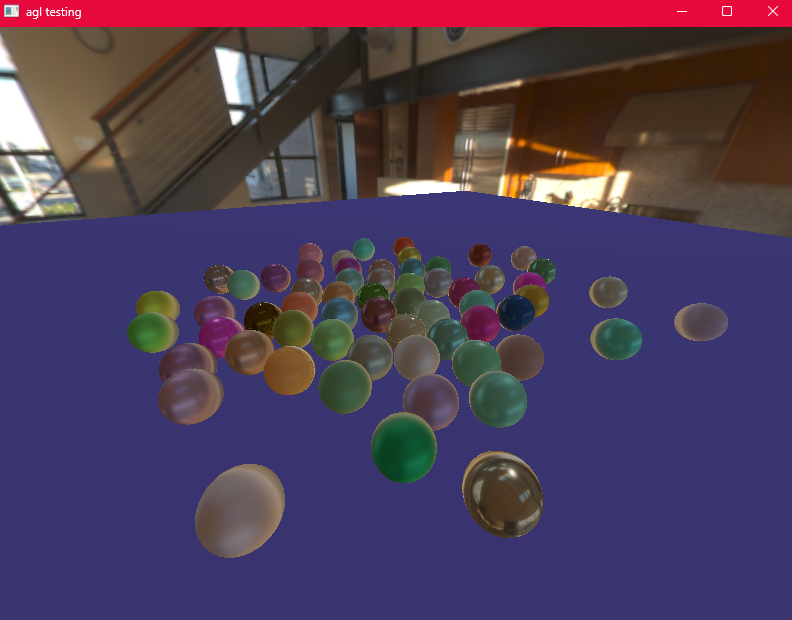

This screenshot shows my first attempts at implementing PBR (physically based rendering) using a tutorial on LearnOpenGL (link to the tutorial series)

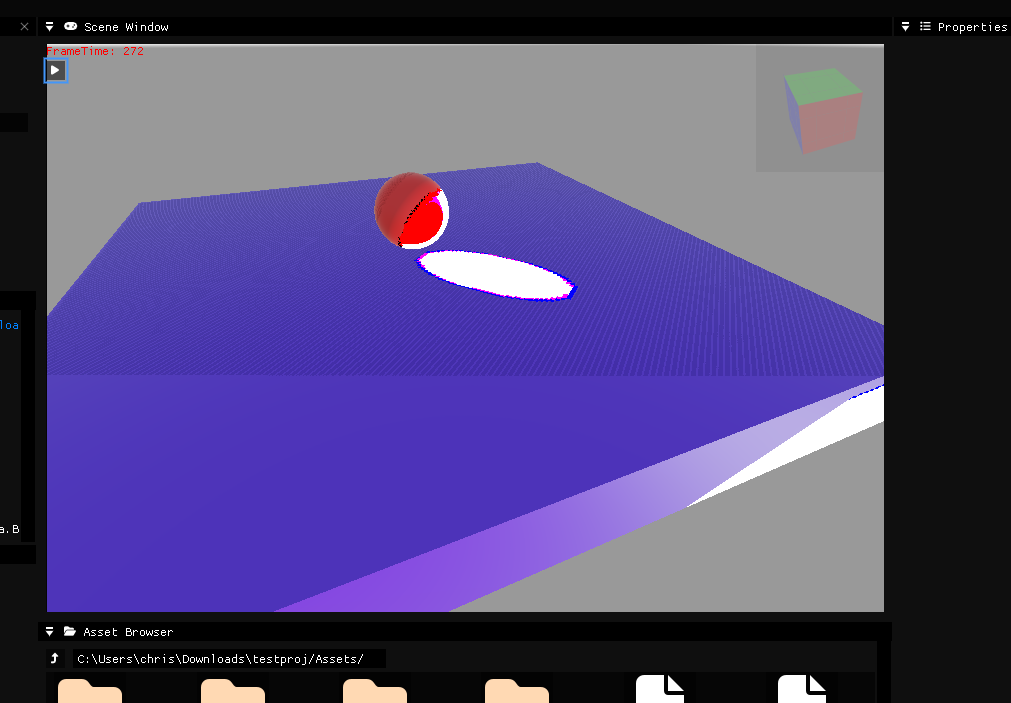

Some concepts such as shadow rendering and skeletal animation were difficult for me to truly grasp (since I was about 13 at the time), and the difficulties I faced with shadows and such are seen in some early screenshots

Part of the reason behind my inability to understand these concepts were because I was just reading the code and implementing it into my engine. Something that would benefit me later into the process would be actually reading the tutorials to understand the concepts.

Moving away from my first iteration

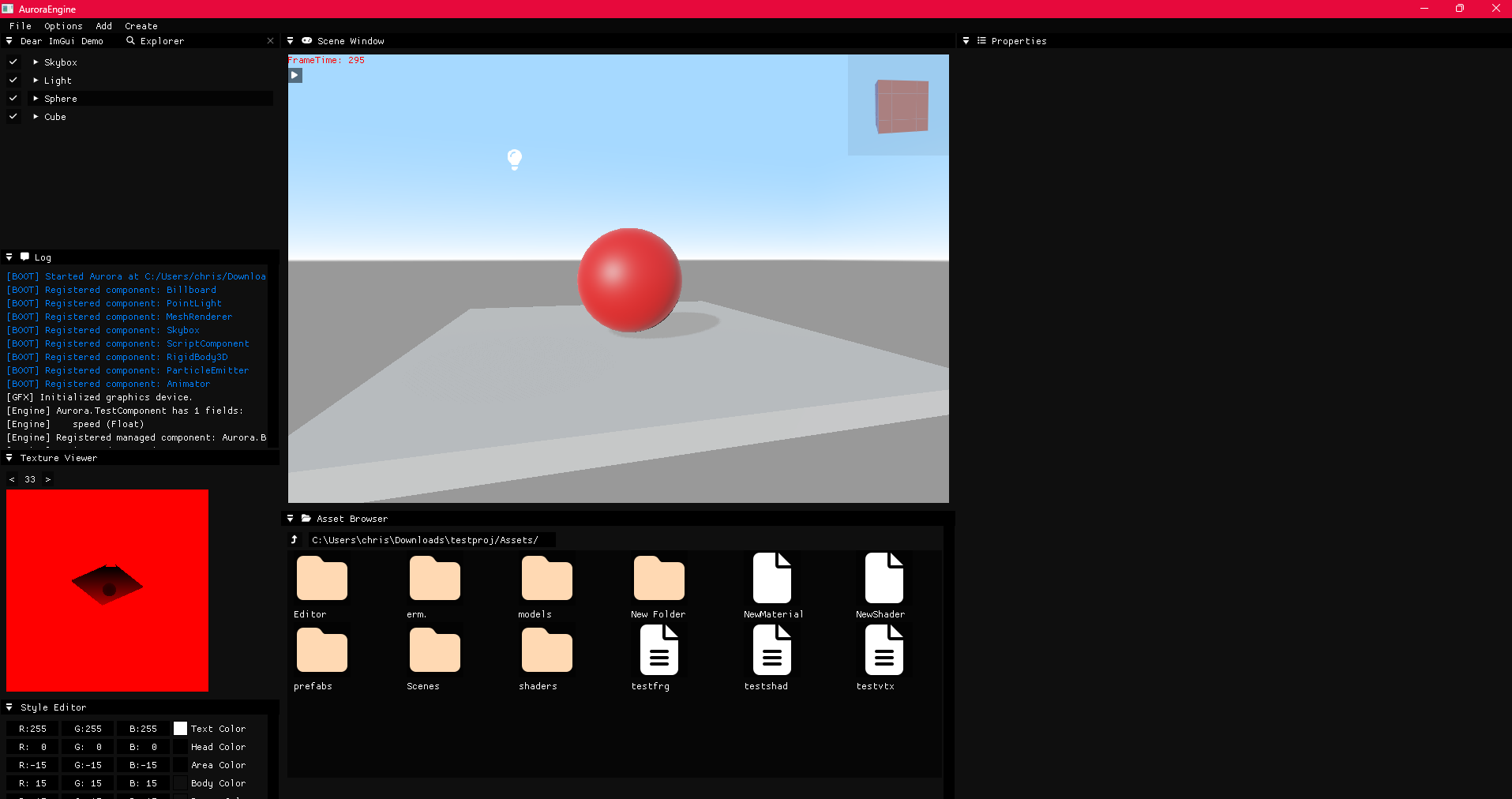

Something that may have caught your eye in these screenshots could be the engine UI shown, using ImGUI, where I really tried replicating the Godot/Unity feel.

While the engine UI was great, it led to me eventually implementing C# Scripting using the Mono Runtime where I was able to directly create scripts and such to program objects, similar to Unity’s MonoBehavior system.

My C# Scripting system worked well, but it caused a major performance drop in the engine, as average frame rates dropped to ~40 FPS, from ~70 FPS.

Looking Back

My main issue other than the performance, was my inability to make games work outside the traditional engine environment. At the time, I was unable to understand that I could just remove the ImGUI context, and allow the game to run without it. My worry was that the engine would be vulnerable, and certain malicious users could inject code into the game(s) I would have been making, and open an engine UI environment, with all the code I used for the engine UI out to use. Keep in mind, I did not understand macros that would obfuscate the visual engine code from the final game, like such

1

2

3

#ifdef USING_ENGINE_UI

void DrawEngineUI();

#endif

If I was to utilize macros like this, then the engine UI code would not be built with the final game, preventing a hacker from using the engine UI.

Still, my scene serialization system and project system for the engine application were the same, so if a user got their hands on a scene file and the engine application, they would be able to load a game scene on their own and edit the game.

While all of these issues are fixable, at the time (November-December 2023), I did not feel like managing all the issues behind having a serialized scene and project system.

Overall, this first iteration of my game engine project was helpful to my C/C++ journey, as I started out knowing nothing about the languages and came out learning concepts that most developers don’t dabble in.

The Second Iteration

Learning from my mistakes

After taking a 2-3 month break near the end of Summer 2024, I restarted on the engine and decided to use bgfx for more compatibility at the expense of documentation & support. Deciding to use bgfx meant that the tutorials provided by LearnOpenGL would have to be translated across rendering libraries.

Now that I had already gone through the process of creating a game engine, I knew what physics & audio libraries to use, how to distribute my time, and how to implement certain features. I decided not to include an engine UI this time, as it took up most of my time around February-May 2024.

BGFX included debug features such as text rendering (which was especially helpful around the start), but lacked compatibility with homebrew environments such as libnx (Nintendo Switch homebrew)

By looking through the examples and reading Discord conversations I was able to rebuild the engine, and it had been empowered by bgfx’s abstraction layers, allowing me to use DirectX, Apple Metal, and other rendering libraries with little to no change in code.

However, since these numerous rendering libraries use different shader languages I did have to modify my knowledge regarding GLSL to fit with BGFX’s proprietary shader language, which could translate to any shader language.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

def build(platform):

print(f"Building for {platform}")

outPath = f"runtime/shaders/{platform}"

if not os.path.exists(outPath):

os.makedirs(outPath)

else:

shutil.rmtree(outPath)

os.makedirs(outPath)

vsf = "-i vendor/bgfx/src/ "

fsf = "-i vendor/bgfx/src/ "

csf = "-i vendor/bgfx/src/ "

if (platform == "dx"):

vsf += "-platform windows -p s_5_0 -O 3"

fsf += "-platform windows -p s_5_0 -O 3"

csf += "-platform windows -p s_5_0 -O 3"

elif (platform == "gl"):

vsf += "-platform linux -p 440"

fsf += "-platform linux -p 440"

csf += "-platform linux -p 440"

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(os.getcwd()):

for file in files:

file_path = os.path.join(root, file)

file_path = convertPosix(file_path)

if (file.endswith(".vbsh") ):

buildShader(file_path, "vertex",vsf, outPath)

if (file.endswith(".fbsh") ):

buildShader(file_path, "fragment",fsf, outPath)

if (file.endswith(".cbsh") ):

buildShader(file_path, "compute",csf, outPath)

The code I used to build shaders simultaneously for every graphics library

Although there were many workarounds needed to get the games to work across graphics libraries, I still believe bgfx is one of if not the best abstracted graphics libraries (better than Google Filament, for me), simply because of the low amount of code necessary to get complex concepts to work, and also because bgfx uses OOP (Object-Oriented-Programming), something I really liked about Vulkan and couldn’t stand about OpenGL.

About the Engine

Project Tomato, or Tomato Engine (not final) has about the same features as the previous iteration (which was named Aurora Engine)

- Dedicated 2D support

- AI Navigation & Pathfinding (deprecated)

- 3D Audio using OpenAL

- Debug UI with ImGUI

- Entity-Component System1

- Lighting System w/ Cube maps

- Networking using enet (WIP)

- Particle Systems (WIP)

- 3D & 2D Physics using bullet & Box2D

- Primitive rendering

- Established UI System w/ buttons, scroll wheels, text boxes, etc.

- Lacks a dedicated editor and C# Scripting

Notes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

struct Object

{

template <typename ObjType>

ObjType* GetObjectFromType();

};

struct MeshObject : Object

{

// MESH CODE HRE

};

TomatoEngine’s Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

struct Component {

struct Object* object;

};

struct MeshComponent : Component {

// MESH CODE HERE

};

struct Object

{

std::vector<Component> components;

template <typename CompType>

CompType* GetComponent();

};

AuroraEngine’s Implementation

While my first iteration (AuroraEngine) had a dedicated class for components, the new iteration (TomatoEngine) uses the Object class for “components”.

Projects I have worked on under the new iteration

The new iteration’s lack of an engine UI and C# Scripting makes it easier to work on games. I learned to produce a final project while developing the engine to fit my needs, so whenever I get to a project or element that needs a certain feature, I will modify the engine to implement said feature.

I have worked on a few projects to test the capabilities of the engine, from an attempted Tomodachi Life fan project (before they announced a sequel), to a recreation of Nintendo’s Tofu Prototype which eventually transformed into Splatoon.

Tofu Demo Recreation

These projects were created solely for learning and experimentation. All external assets are credited to their original owners where applicable. These projects are not publicly available.

The Entity Component System technically is not an ECS, as unlike the first iteration, it’s not a traditional one similar to flecs or Unity’s GameObject system. ↩︎